You might be planning to cross the Nullarbor to watch whales, or to have an exciting camping experience, but did you know that the Nullarbor is also home to some of civilization’s oldest artifacts? Yes, and the great news is that you could include “witnessing history unfold” in your crossing-the-Nullarbor itinerary.

Of the Nullarbor and Its People – The Stories Caves Tell

European settlers, upon arrival, have considered the Nullarbor to be almost uninhabitable. The arid area, at first glance, is a challenge for any living thing, the name itself is Latin for “no trees” — it’s a stretch of desert-like environment 2,000 kilometres across. However, before it became the Nullarbor, it was first the “Oondiri” — the waterless — to the Spinifex and Wangai people, who have managed to inhabit the area and proved that it actually provided enough to sustain life.

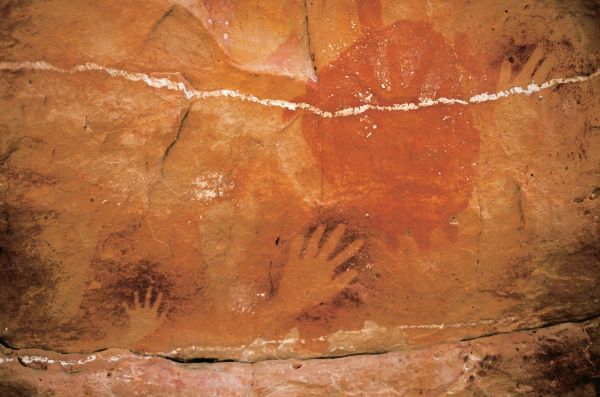

In 1956, Dr. Alexander Gallus found and studied drawings in the Koonalda Cave — the first markings of their kind to be reliably dated to the Pleistocene epoch (the ice age) over 22,000 years ago. The markings were found 300 metres from the entrance, where there was no natural light.

The cave markings consist of random criss-crossing parallel finger markings, with large groups of vertical lines, and occasional horizontal lines in some parts, and some circular patterns. Some of the lines even depict larger images believed to be symbols: a herringbone pattern that is 120cm long, with 74 diagonal incised lines, above which are 37 short finger markings all believed to be deliberate, because the number of lower lines is exactly twice the number of upper lines.

These wall markings in the Koonalda cave redefined contemporary understanding of the ‘age’ of Aboriginal art in Australia, and the world, and humanity’s inherent desire to tell stories.

The Spinifex people, some of the oldest inhabitants of the Nullarbor, have largely maintained their hunter-gatherer lifestyle up to the present, and all of the history it carries. They’re known for their art, boldly colored “dot paintings” that depict the sun, the soil, the desert and the sky, some of which have been showcased in major art exhibitions in London.

The Wangai people, on the other hand, have played a major role in the discovery of not only water, but gold in the area. The Mirning people, from the coastal region of the Great Australian Bight, some of the earliest people known to practice circumcision and subincision, have beautiful myths narrating the relationship between people and the great whales that live in the area’s waters.

The Dreamtime

Australian Aboriginal mythology repeats a theme that echoes up to the present: the story of transience, of passing by, of adventure. Creation, according to Australian myths, is a by-product of culture heroes who traveled across a formless land, creating sacred sites and significant places of interest in their travels. The “Dreaming” is the plane where these heroes exist – a “time out of time,” the existence before birth, and after it. A beautiful example of this is the creation myth in the Nullarbor.

The Sun Mother is asleep in a cave beneath the Nullarbor plain, and the Great Father Spirit woke her, telling her to leave her cave and stir the universe into life. The entire world was dark, and the moment she opened her eyes, she bathed the world in rays of beautiful sunlight. When she took a breath, the world kissed its first breeze. She started a journey, creating grass, shrubs and trees wherever her rays touched the ground. She found living creatures: insects, lizards, and marsupials sleeping under the earth, as she did, before the Great Father Spirit woke her. So she woke these creatures too from their slumber, and asked them to spread throughout the trees and grasses. Great rivers flowed behind the snakes, teeming with life.

One day, as all the creatures watched, the Sun Mother traveled far to the West, painting the sky red to black until darkness returned to the land. The creatures huddled together in fear.

But sometime later she returned, once again painting the sky yellow and blue. The creatures understood that darkness was a time for rest, and that she will always, always come back.

So when you lie down on the ground and look up to the great starry Nullarbor sky and its clear horizon, remember: it’s the same magnificent sight people from thousands of years ago marveled at, and chose to capture and remember. It’s a testament to how life persists, life flourishes, life dares to dream, regardless of how hard the circumstances might prove to be.

If you want to know more about the Nullarbor’s rich culture and history, feel free to reach out. Nullarbor Roadhouse is more than happy to show you around.

Sources:

Rare Aboriginal heritage of the Nullarbor Plain included in the National Heritage List